Physical Quantities

1. Basic Idea

A physical quantity is anything that can be measured.

Examples: length, weight, time, temperature.

When we measure something, we must write:

- A number

- A unit

For example:

- 5 meters

- 3 seconds

- 2 kilograms

The number tells how much.

The unit tells what type of measurement.

If we only write the number and do not write the unit, the measurement becomes unclear.

Common Units

| Physical Quantity | Unit (Commonly Used) |

|---|---|

| Length | meter (m) |

| Mass | kilogram (kg) |

| Time | second (s) |

| Temperature | degree Celsius (°C) |

| Electric current | ampere (A) |

Scientific Notation

Very large and very small numbers are difficult to write and read.

To make them simple, we use scientific notation.

Scientific notation means writing a number as:

a × 10n

where a is a simple number and n is a whole number.

Examples:

- 0.00034 becomes 3.4 × 104

- 154000000 becomes 1.54 × 108

Scientific notation reduces the chances of mistakes when writing many zeros.

Step-by-Step Conversion to Scientific Notation

Example 1:

0.00052

Move the decimal to make it 5.2

Count places moved: 4 places to the right

So it becomes:

5.2 × 10-4

Example 2:

72000000

Move the decimal to make it 7.2

Count places moved: 7 places to the left

So it becomes:

7.2 × 107

SI Quantities and Base Units

1. Need for One System of Units

In different countries, different measurement systems were used in the past.

This created confusion because values had to be converted again and again.

To avoid confusion, scientists agreed to use one common system of measurement worldwide.

This system is known as the International System of Units.

Its short form is SI.

SI is based on the metric system.

This means measurements are done using meters, kilograms, and seconds.

2. Base Units

In SI, there are some basic quantities that cannot be broken into simpler measurements.

These are called base quantities.

Each base quantity has one fixed unit known as a base unit.

The seven base quantities and their units are:

| Quantity | Unit | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| Mass | kilogram | kg |

| Length | metre | m |

| Time | second | s |

| Electric current | ampere | A |

| Temperature | kelvin | K |

| Amount of substance | mole | mol |

| Luminous intensity (light strength) | candela | cd |

Why Base Units are Important

To measure something correctly, the unit should be clear and fixed.

Base units give a standard that is accepted everywhere.

This makes communication and calculations easy and accurate.

Multiples and Sub-multiples of Units

| Prefix | Symbol | Meaning (Multiplying Factor) |

|---|---|---|

| tera | T | ( 1012 ) |

| giga | G | ( 109 ) |

| mega | M | ( 106) |

| kilo | k | ( 103 ) |

| deci | d | ( 10-1) |

| centi | c | ( 10-2) |

| milli | m | ( 10-3 ) |

| micro | µ | ( 10-6) |

| nano | n | ( 10-9) |

| pico | p | ( 10-12) |

What are Derived Units

There are some quantities which are measured directly.

Examples: length (metre), mass (kilogram), time (second).

These are called base quantities and have base units.

All other quantities in physics can be written using these base units.

These are called derived quantities, and their units are called derived units.

Key Point

Derived units are formed by multiplying or dividing base units.

They are never formed by adding or subtracting base units.

Example:

- The unit of speed is metre per second (m s⁻¹).

- It is formed by dividing length (m) by time (s).

| Quantity | Unit (Name) | Derived Unit Form |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | hertz (Hz) | s⁻¹ |

| Velocity | m s⁻¹ | m s⁻¹ |

| Acceleration | m s⁻² | m s⁻² |

| Force | newton (N) | kg m s⁻² |

| Energy | joule (J) | kg m² s⁻² |

| Power | watt (W) | kg m² s⁻³ |

| Electric charge | coulomb (C) | A s |

| Potential difference | volt (V) | kg m² s⁻³ A⁻¹ |

| Electrical resistance | ohm (Ω) | kg m² s⁻³ A⁻² |

| Specific heat capacity | J kg⁻¹ K⁻¹ | m² s⁻² K⁻¹ |

Errors and Uncertainties

Introduction

In every measurement, there is always some level of uncertainty. This uncertainty arises because no measuring instrument or technique is perfectly accurate. Understanding errors and uncertainties helps us judge how reliable our measurements are and how much we can trust the results.

Uncertainty is the doubt about the exactness of a measurement.

Meaning of Error

An error is the difference between the measured value and the true value of a quantity.

Errors can occur due to limitations of instruments, incorrect observation, or changes in the environment during measurement.

Errors are generally divided into two main types:

Random errors

Systematic errors

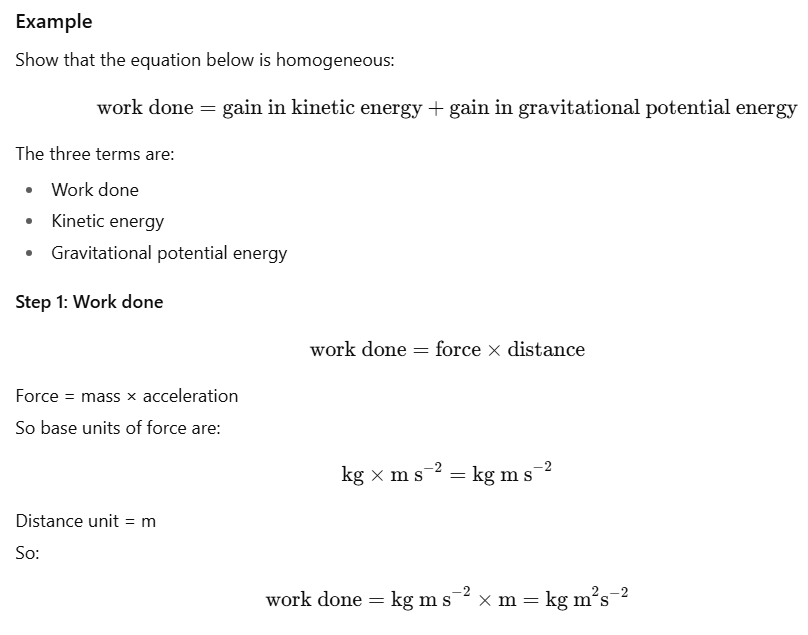

Topic: Checking Equations

(Homogeneous Equations)

1. Why Do We Check Equations

In physics, every equation must make sense not only by numbers but also by units.

Each term in the equation must have the same base units.

If the units do not match, the equation is incorrect.

2. Meaning of Homogeneous Equation

When every term in an equation has the same base units, the equation is called homogeneous or balanced.

If the equation is not homogeneous, it cannot be correct.

Example:

[

v = u + at

]

Here:

- ( v ) has units m s⁻¹

- ( u ) has units m s⁻¹

- ( a ) has units m s⁻² and ( t ) has units s

So ( at ) = m s⁻² × s = m s⁻¹

All terms have the same unit m s⁻¹.

So the equation is homogeneous.

3. Why This is Useful

Once we know the equation is homogeneous:

- We can trust that it makes physical sense.

- We can use the base units to find the unit of an unknown quantity.

Example

Scalars and Vectors

Meaning of Physical Quantities

- All physical quantities have magnitude and unit.

- Some quantities also require direction to be fully described.

Scalar Quantities

- Definition: A scalar has magnitude only.

- Examples: mass, speed, temperature, pressure, time, distance.

Vector Quantities

- Definition: A vector has magnitude and direction.

- Examples: velocity, acceleration, force, displacement.

| Quantity | Scalar | Vector |

|---|---|---|

| Mass | ✔ | |

| Weight | ✔ | |

| Speed | ✔ | |

| Velocity | ✔ | |

| Acceleration | ✔ | |

| Force | ✔ | |

| Pressure | ✔ | |

| Temperature | ✔ |

Vector Representation

Understanding the Need for Direction

Some physical quantities are not completely described by a number alone.

For example, when you hit a tennis ball, simply knowing how hard you hit it is not enough.

You must also know which direction the ball moves in.

This shows that the force you apply has both:

- magnitude (how strong the push is)

- direction (where the push is aimed)

Any quantity that needs both magnitude and direction is a vector quantity.

How Vectors Are Represented

The most common way to represent a vector is by using an arrow.

The arrow provides two important pieces of information:

- Direction: shown by the direction in which the arrow points.

- Magnitude: shown by the length of the arrow.

A longer arrow means a larger magnitude, and a shorter arrow means a smaller magnitude.

Using Scale to Represent Magnitude

When drawing vectors, a scale is chosen so the length of the arrow correctly represents how large the vector is.

Example scale:

- 1 unit of arrow length = 5 m s⁻¹ (meter per second of velocity)

So:

- If a velocity is 15 m s⁻¹, the arrow must be drawn 3 scale units long.

- If a velocity is 10 m s⁻¹, the arrow must be drawn 2 scale units long.

This keeps vector diagrams clear and accurate.

Addition of Vectors

Adding Scalar Quantities

Some quantities depend only on size.

These are scalar quantities.

To add scalars, we simply use ordinary addition because direction does not matter.

Example:

A beaker contains 250 cm³ of liquid and another contains 9.0 litres.

Since 1 litre = 1000 cm³, the total volume becomes 250 cm³ + 9000 cm³ = 9250 cm³.

So scalar addition is straightforward.

Why Vector Addition Is Different

Vectors have both:

- magnitude (size)

- direction

So we cannot just add their numbers directly.

Direction must also be considered.

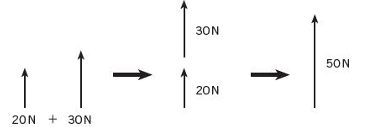

Vectors in the Same Direction

If two vectors act in exactly the same direction, their magnitudes can be added directly.

Example:

Weight 20 N and weight 30 N both act upward.

Combined weight = 20 N + 30 N = 50 N.

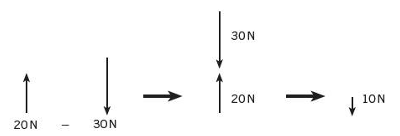

Vectors in Opposite Directions (Negative Vector)

If two vectors act in opposite directions, their magnitudes are subtracted, and the direction is the direction of the larger vector.

Example:

20 N to the Up and 30 N to the Down

Resultant = 20 N to the Down.

Angle Between Vectors

If the angle between two vectors is:

- 0° → they act in the same direction, resultant is maximum.

- 180° → they act in opposite directions, resultant is minimum.

- Any angle in between → resultant value lies between those two extremes.

This resultant vector is called the combined effect of the vectors.

Vector Triangle Method

When Vectors Are Not in a Straight Line

If two vectors do not act along the same line, we use a vector triangle to find the resultant.

How It Is Represented

Each vector is drawn as a straight arrow:

- length of arrow shows magnitude

- direction of arrow shows actual direction

Place the tail of one vector at the head of the other.

This forms two sides of a triangle.

The third side of the triangle gives the resultant vector:

- It is drawn from the tail of the first vector to the head of the second vector.

Direction Rule

When drawing:

- If both vectors are drawn clockwise, the resultant is anticlockwise.

- If both vectors are drawn anticlockwise, the resultant is clockwise.

This ensures correct final direction.

How to Find the Resultant

You can:

- Measure the resultant by scale drawing (practical diagram method), or

- Use trigonometry (mathematical method) if angles and lengths are known.

Summary

- Scalars add directly because direction is not involved.

- Vectors require direction to be considered during addition.

- If vectors act in the same direction → add magnitudes.

- If in opposite directions → subtract magnitudes.

- If vectors form an angle → use the vector triangle method.

- The resultant shows the final combined magnitude and direction.

Vector Triangle Experiment and Addition of Multiple Vectors

Resolution of Vectors

Need for Resolution

In many situations, instead of combining vectors, we need to break a single vector into parts. This process is called resolution of vectors.

A vector can be resolved into components, usually along perpendicular directions (for example, horizontal and vertical).

By doing this, we can study how much of the vector acts in each direction, which simplifies problem-solving in physics and engineering.

Concept of Components

The parts into which a vector is resolved are called its components.

When a vector is resolved, the combined effect of its components is exactly equal to the original vector.

So, resolution doesn’t change the actual physical effect—it only helps analyze it conveniently along chosen directions.

Resolution of a Force

Consider a force of magnitude F acting at an angle θ below the horizontal.

This force can be resolved into two perpendicular components:

- A horizontal component, Fx

- A vertical component, Fy

These components form a right-angled triangle with the original force as the hypotenuse.

Mathematical Expressions

F_x = F \cos \theta F_y = F \sin \thetaHere:

- F_x is the horizontal component of the force.

- F_y is the vertical component of the force.